Should We Be Making Our Students Do Presentations?

A graphic of two people exhibiting an idea.

October 28, 2021

It’s a Monday morning and you can’t stop shaking. There’s a sense of incoming dread lingering within you. You know you haven’t done anything wrong– quite the contrary, in fact. You’re all caught up with your work. Many might even say you’re one step ahead. All the information you had to know was engraved into your mind, so why were you struggling to showcase that in front of the class? It seems that the capacity to speak in public is no longer one of the many pathways to success; it’s a tightrope that you’re required to cross.

When it comes to doing oral presentations, many students find that it’s a major struggle, especially those who may suffer from anxiety or speech disorders. At the same time, many believe presentations help challenge students and may strengthen their speaking capability. One question remains: Is the challenge necessary? Is there not any other way to allow students to build their ability to verbally convey things? Does it help to force students to stand in front of a class of 10-30 pupils?

When I was younger, I was shyer than I’d care to admit. Thinking about presenting an idea to more than one person at a time made me want to hurl. Even so, it wasn’t hard to see that I was one of the smartest students at my old school. I just had trouble showing that verbally. Having to be analyzed based on my ability to keep myself from stumbling over my words or fidgeting was never something I looked forward to. I felt trapped every time I had to present. There were so many other factors I had to consider alongside the actual information I had to talk about. It was overwhelming.

I was stuck in my own little shell, and I truly had no intention of breaking out of it.

I was actually forcibly driven out of my shell, if I’m being honest. It all happened because my drama teacher approached me a week before auditions for the school play.

“You’re going to audition,” he said, clearly determined. “You have no choice. You have to show up.”

It’s safe to say I was horrified. I don’t know why he chose me of all people to force into this situation. I had no prior drama experience, nor was I good at enunciation, or projecting my voice, or anything speaking-related for that matter. I had no idea what he saw in me. Nonetheless, I showed up on audition day, despite the fear that swallowed me alive.

On the day of the audition, I remember seeing a group of kids lined up outside the music room. This just made my anxiety grow. Surprisingly, I didn’t walk out last minute. After an hour or so of waiting behind what felt like trillions of students, I walked into the audition room with a few of my classmates and some other students I didn’t know. I was shaky and overall very quiet. My palms were sweaty as I was handed the script. Despite my obvious nervousness, I gave it my all and tried to sound confident as I read out the lines given to me. I tried to mimic the actors in the plays I’ve seen before, speaking as loudly and clearly as I possibly could have. The audition carried on for what felt like hours, but afterward, I walked out of that room feeling both relieved and content as if the weight of a thousand bricks had been lifted off my shoulders.

I got the lead role. I had no idea how, but the drama teacher saw something in me that I couldn’t see in myself.

Because of that experience, I found a love for acting, where my adoration for public speaking began. I felt like a completely different person when I was performing, and I never would have found that love if it wasn’t for my teacher forcing me to present myself in front of my peers. I learned a lot of valuable skills from my time performing in this play, and to this day I thank my old drama teacher for pushing me outside of my comfort zone.

However, my experience isn’t a shared one.

Teachers, please stop forcing students to present in front of the class & raise their hand in exchange for a good grade. Anxiety is real.

— @DAMNBlEBERS via Twitter

“My personal experiences with in-class presentations are mostly negative,” explained a freshman at ILS, who requested to stay anonymous. “As a child, I enjoyed them because they weren’t too difficult. As I got older, my mental and physical problems got far worse and I am barely able to do so now without having some sort of problem.”

Many students were shoved into similar conditions, where their mentors would push them to do something they felt uncomfortable doing. While this circumstance could have a positive outcome, such as my own, that most definitely isn’t the case with a lot of students.

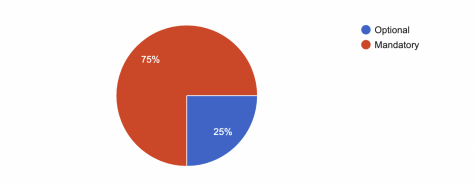

ILS sophomore Isabella Costa is among the many students who believe in-class presentations should be optional. She found that while giving presentations has helped her improve her speaking skills, that isn’t the case for a lot of students.

“There are many students that struggle with public speaking. While giving presentations may help them improve and show their understanding of a topic, as well as help their ability to speak, their grade in the class should not depend on it,” explained Costa.

Presentations like this could be especially difficult for students suffering from physical or neurological difficulties. “People with GAD (General Anxiety Disorder) often come into difficult situations during social activities. Many people who are neurodiverse experience similar problems, i.e. being overstimulated very quickly or running into a meltdown midday. People without proper diagnoses can experience the same thing. The same goes for people without up-front problems, too.” explained the same freshman, proposing an alternative: “Assigning class presentations with an option between presenting it in front of everyone or having a teacher pull up a slide with text-to-speech/text on the screen would drastically decrease mental distress in class.”

An ILS sophomore, who asked to remain anonymous, had a contrasting opinion. As someone who reads at church and volunteers at many public speaking events, she firmly believes in-class presentations should be mandatory.

No matter what your job is, you’re going to have to give presentations The whole point in school is for them to prepare you for college and for life.

— Anonymous ILS Sophomore

All the teachers we interviewed had a similar point of view. One of those teachers was Mrs. Laura Moya, the freshman guidance counselor. “I did not have to do class presentations until I got to college, and I was terrified and inexperienced, so I think practicing in high school would be beneficial,” she revealed.

Mrs. Ana Roman-Gonzalez, an English teacher, also believed in-class presentations should be mandatory. “I was deathly afraid of speaking in public while I was in my freshman and sophomore year but by junior and senior year, after much practice, I conquered my fear. I ended up running for student body president and won! I also had to give the valedictorian speech at the end—Thank God I had plenty of practice by then,” Mrs. Roman said. “Although oral presentations make some students cringe, they are an essential part of the ELA curriculum which is all about communicating ideas using various platforms. I believe it’s a skill that, when mastered, helps a person succeed.”

Opinions on this topic vary greatly, but the overall consensus is that in-class presentations help students develop skills they may need in the future and that it’s much more beneficial to develop these skills earlier on rather than later. However, it’s important to take into consideration the mental health of all students. Perhaps the implementation of alternative methods of oral presentation could create a common ground between the two stances.